12th Century Interest Rates

Author: Kent Polkinghorne

Source material: A History of Interest Rates, Fourth Edition by Sidney Homer and Richard Sylla (1963, 2005). This book covers interest rate history dating back to ancient times and contains very interesting charts, tables, and analysis which I will attempt to modernize and summarize. This data can expand our understanding of different eras of monetary and financial information to make us better investors.

Prelude to the 12th Century

After centuries of low growth, sound money, in the form of Byzantine and Arab gold coins, began to find its way back into western Europe. This increased flow of money was followed by a revival of trade in 11th and 12th centuries. However, the philosophy on usury that had been formed during the Dark Ages persisted and continued to play a large role in governing trade.

More reliable record keeping also returned in the 12th century which will allow a more detailed study on the interest rates of this period. In this article we will focus our attention on a number of topics such as usury, money and credit, forms of credit, and of course interest rates as they relate to the 12th century. As the reader might recall from the previous missive on dark age interest rates, the interest rates themselves were not recorded. The most plausible reason for their absence was probably to avoid the stigma associated with usury. It is likely that keeping records would have served as an obvious form of self-incrimination. Either way, interest rate records returned in the 12th century although they were not as detailed as in the centuries to come.

To begin today’s study, we will again focus on the topic of usury but through the lens of the 12th century.

Usury in the 12th Century

The topic of usury, as understood through the lens of the Roman Catholic Church, continued to play a key role in governing the behaviors of medieval European citizens. In fact, the intellectual framework around the subject was expanded and also became more detailed and specific in the 12th century. As a result, before we move on to the subjects of money, banking, and interest, it is important to have a thorough understanding of the philosophies that underpinned the issuing of medieval credit.

In 1139, the Second Lateran Council banned usury and heaped scorn on those who partook. In essence, adding a layer of social pressure on top of the ban itself. Pope Eugene III (c. 1080 – 8 July 1153) declared that

“mortgages, in which the lender enjoyed the fruits of a pledge without counting them toward the principle, were usurious.”

Eugene appears to be referencing a situation where a borrower posts land as collateral in exchange for a money loan. In his example, the lender of the money would benefit from the produce of the borrowers land, such as the produce from a tomato farm, however, the produce from said tomato farm would not have been counted toward repayment of the principal. This situation was defined by Eugene as usurious and was seen as theft and therefore restitution would be required. The ability to more clearly define instances of usury during the 12th century was an improvement from prior centuries and more clarity on the topic would follow.

Pope Alexander III (c. 1100/1105 – 30 August 1181) declared that any sales on credit with a price above that of the cash price were usurious. In other words, if an item was purchased on credit then the lender could only break the purchase price into installments whose sum could not exceed the purchase price itself. In contrast, purchasing a car today, for example, involves a series of payments as well but the attached attached interest rate on the car loan would increase the cost of those payments over and above the purchase price itself.

Usury was not considered just sinful by the time of the 12th century but also as an invasion of property rights. The sin of usury weighted heavily on the minds of everyone, from clerics to merchants, and great efforts were made to avoid it. The effort to avoid usury actually led to the development of credit forms which were designed to avoid the sin altogether. As we move forward with our study it is important to keep in mind the prevailing psychology of both borrowers and lenders during this time in order to have a better understanding of how money and credit operated.

12th Century Money and Credit

As mentioned earlier, economic growth in western Europe had greatly improved by the time of the 12th century. The increase in commerce created the need for large markets that could more efficiently connect buyers and sellers. The Fairs of Champagne solved this need by bringing together merchants from all over western Europe. There were six fairs in total with each fair consisting of six weeks. During the fairs, kings allowed usury to be charged as long as the fixed maximum rates of interest were obeyed. Letters of credit were used to guarantee future payment from buyers to sellers. This was an important tool because during those times a purchase would have been made at one fair but not paid in full until the next, thus allowing the buyer the opportunity to run off with the goods never to be seen again. Letters of credit solved this problem because they involved guarantees that, in the event of non-payment by the purchaser, the bank itself would make the merchant whole. These letters of credit were essentially like promissory notes today.

We previously mentioned that during the dark ages the power of cities declined while the power the estates increased. By the time of the 12th century, the trajectory was again reversing due to the transition from manorial to urban industry. Due to rampant currency debasement, the value of money had also declined but this had a positive impact on the welfare of serfs since they would know the value of the future payment owed to their lord in advance and then be able to pay back that payment via a weaker currency. As is true today, currency debasement allows the debtor to more easily pay back their debts. It is probable that serfs were taking advantage of this currency debasement to purchase their freedom and then subsequently move themselves to cities in search of better opportunities.

Although this articles focus is on the whole of Europe, the 12th century really belonged to the northern Italians in terms of banking and finance. By this time, maritime insurance was already well developed in northern Italy and merchants were also receiving deposits as well as arranging foreign remittances. Additionally, wealthy merchants were making loans, secured by land and homes, forming a rentier class in the process. The banks of northern Italy dominated European finance and had branches all over Europe, however, another soon to be dominant participant was also trying to make a name for itself in continental finance, the Flemish. For example, in addition to receiving financing from Italian banks, the growing wool industry of England was also being financed by the rapidly growing Flemish banks. The Italians and Flemish would go on to dominate not only banking but also other areas, such as art, for centuries to come.

In addition to the letters of credit previously mentioned, there are two other important forms of credit that were widely utilized during the 12th century. We will explore those credit forms next.

Credit Forms

Two of the most important credit forms that were active in the 12th century were pawnshops and bills of exchange. Pawnshops would issue credit in exchange for a pledge i.e., some form collateral. In order to secure a loan from a pawnshop one would need to offer some form of security to the lender which in most cases was land. Bills of exchange were similar to modern promissory notes but we will need to use an example to understand them better.

Using the Fairs of Champagne as our backdrop, let’s say someone purchases goods from a merchant at one of the fairs. If the purchaser did not have the money to pay for the goods when the exchange was made then a bill of exchange would be drawn up by the purchaser with a promise to pay for the goods at the next fair. The merchant (or seller) would keep this bill and then present it at the next fair to receive settlement.

Bills of exchange and the letters of credit discussed earlier are very similar, however, there are a couple differences. Letters of credit contain promises by a bank that if the buyer cannot pay for the goods then the bank will be liable, however, a letter of credit is not the payment itself. In the case of a bill of exchange, it essentially functions like a modern check and can be used by the payor to pay for goods and services. The bill of exchange is a negotiable instrument and can be used to settle an account or even be transferred from one owner to the next.

Up to this point in the article, we have been focusing on the topics of usury, money, and medieval credit forms which provided us with the context necessary for moving on to our final section of the study. We can now shift our focus to the 12th century interest rates themselves.

Background on 12th Century Interest Rates

As we observed earlier, one of the reasons that data on interest rates from around this era is sparse is likely due to the stigma one would derive from having kept them, nonetheless, the 12th century finally provides us with some data after a long hiatus. During this time, money lending in England for example was largely carried out by Jews and they provided posterity with two sets of rates: the first set applied to borrowers with good security (collateral) while the second applied to borrowers with poor security. Rates charged to borrowers with excellent security were 43 1/3% on an annual basis, or 52% if compounded. If the security was poor then rates could fluctuate anywhere between 80-120%. Due to the short term nature of loans, interest was recorded on a weekly basis. Continental pawnbrokers also generally charged 43 1/3% but their rates could go higher as well. An example of a of a loan recorded in the 12th century is provided in the text:

“An Englishman, Richard of Anestey, borrowed from moneylenders to sustain his claim on his uncle’s estate; he paid an average of just under 60% a year.”

By end of the 12th century, commercial and official loans in the Netherlands were reported at rates between 10% and 16% annually while a record from the year 1200 in Genoa indicates that Genoese banks were charging 20% for their loans. Bottomry loans were reported between 43-50% but the text doesn’t include this type of loan along with the other interest rates provided because, in the event of a shipwreck, the lender would have had no recourse except to fully assume the loss.

A unique situation occurred in the city of Genoa in 1164 whereby the municipality itself promised future revenues to investors in exchange for loans in the present but, sadly, the interest rates associated with these types of loans were not provided. These municipal loans were eventually packaged together along with the rest of Genoas municipal debt and the Bank of St. George (Casa di San Giorgio) would assume responsibility for managing the debt. This bank is apparently famous in large part for its' role in financing the rise of Genoa whereby merchants pooled together large amounts of resources and then loaned them to the city in order to finance sea voyages. Genoas’ shipping industry would go on to dominate the Mediterranean and would later produce famous explorers such as Christopher Columbus.

In 1171, Venice issued a loan whereby wealthier citizens were forced to purchase the governments’ debt in exchange for a bond, however, regular interest payments were not made. This innovation, if one would call it that, was the precursor to the funded debt of Venice, known as the Prestiti, which we will cover in later articles.

The innovations in finance occurring in northern Italy during the 12th century would continue to grow and multiply. As we will see later installments, government issued debt would become a permanent fixture across the financial landscape, not only on the Italian peninsula, but worldwide.

12th Century Interest Rates

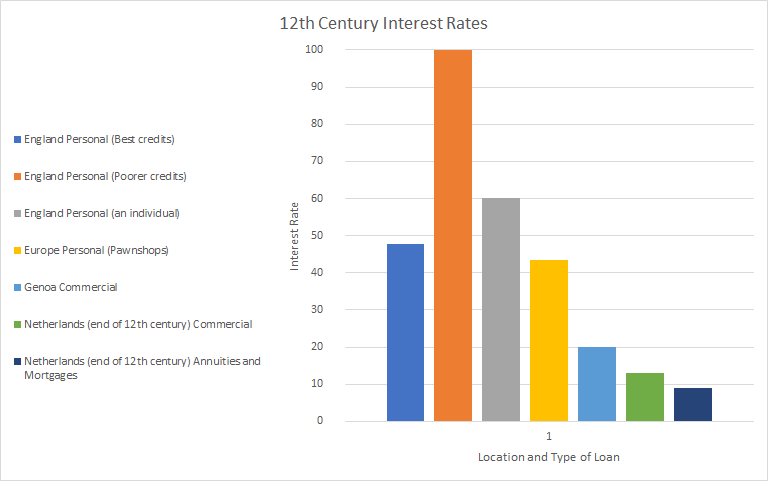

A chart for interest rates in the 12th century is provided below but there are a few notes to keep in mind as you observe the chart. When the text provides both the low end and high end of an interest rate range, we will add those two rates together for our purposes. The types of loans provided in the chart include the following: personal loans from individuals, personal loans from pawnshops, commercial loans, and annuities and mortgages as well.

As to be expected, personal loans carried much higher interest rates than commercial loans. Additionally, borrowers with poor credits had to endure a much higher cost of credit than any other loan type. It is also worth noting that loans in England carried much higher interest rates than did loans in Genoa or the Netherlands. This is perhaps the result of the fact that financial markets were far more advanced in the latter countries than in England. England at this time was not far removed from the Battle of Hastings (1066), which had changed England fundamentally, and was still centuries away from reaching its' peak power.

As the 12th century transitioned to the 13th, new forms of credit would appear along with better records. The 13th century will be the subject of next week’s missive.

Previous in series

- Dark Ages Interest Rates: 5th - 11th Centuries

- Roman and Byzantine Interest Rates – The Byzantine Empire 395 to 1453 A.D.

- Roman and Byzantine Interest Rates - The Roman Empire 27 B.C. to 476 A.D.

- Roman and Byzantine Interest Rates - The Roman Republic 500 B.C. to 27 B.C.

- Ancient Greek Interest Rates

- Mesopotamian Interest Rates: 3000 - 400 BC