A Response from Team Transitory

Was inflation transitory or not? It seems so, but what were the reasons and excuses now offered by the other side. A response to a AIER post.

A post from the American Institute for Economic Research (AIER) was recently shared with me in our community on Telegram. It's titled, Two Kinds of Transitory Inflation. I thought I'd write a quick response to the author Alexander Salter. So, here it goes.

First type of transitory

Right off the bat, he is grouping a variety of people and ideas into a monolithic "Team Transitory" to create a straw man. This is the first type of transitory he wants to dispose of. He pigeon holes the definition of inflation as CPI or PCE right up front, instead of substantively addressing money supply and root causes. He also narrows Team Transitory into a myopic supply-side argument that should properly be imbedded in a broader demand-side and monetary realist perspective.

Set up:

"Team Transitory argued the uptick in inflation beginning in Spring 2021 was primarily due to supply-side factors. Lingering pandemic bottlenecks increased the cost of producing and distributing goods in general. Since these bottlenecks would soon ease, members of Team Transitory assured us, inflation would be short-lived."

Taking down the straw man:

"It has since fallen, but the price level has not. This is important because the supply-side inflation theory does predict a declining price level. If bottlenecks were the cause of inflation, eased bottlenecks should have brought prices back down to where they would have been had the bottlenecks never occurred. To the contrary, the price level remains permanently elevated."

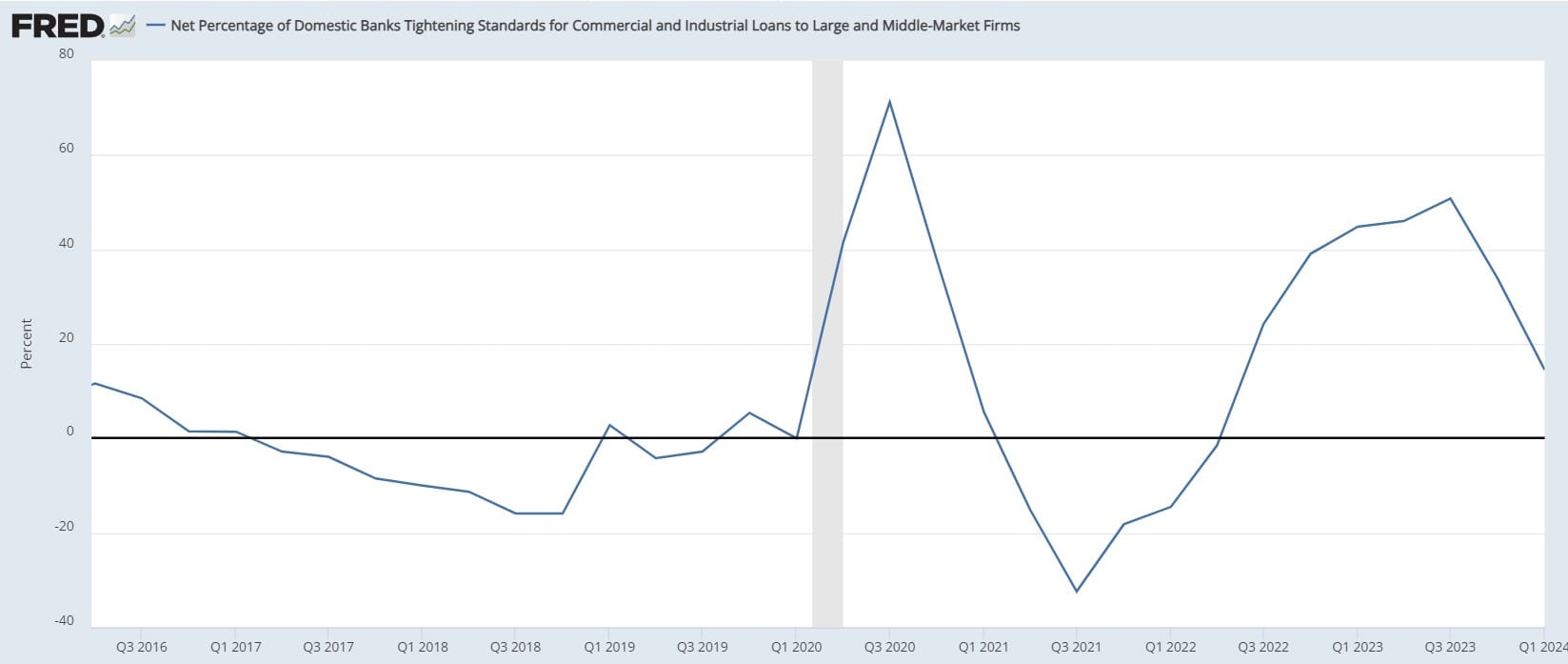

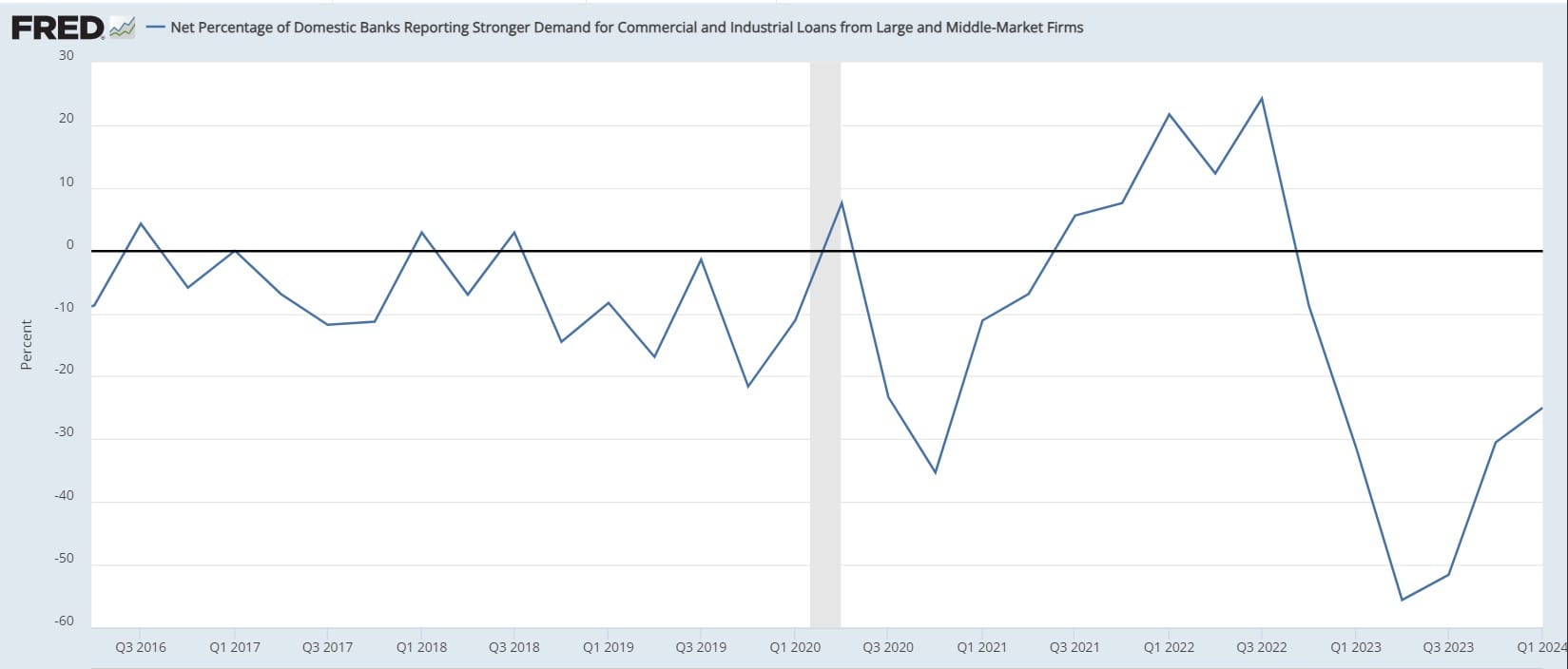

In a binary world, I would consider myself in the transitory camp, but I have explained a detailed position he does not address. For example, new high levels of government spending temporarily make the economy appear more healthy, causing people to lend and borrow more, which is actual inflation. We can see this clearly on the Fed's SLOOS data.

SLOOS measures tightening or loosing lending standards, and rising and falling demand for loans. The first chart below is the lending standards for commercial and industrial loans to medium-large companies. You can obviously see a reaction in 2021 to government programs and guarantees, banks radically loosened lending standards.

Demand for commercial and industrial loans followed the same path (mirror image). Demand for loans skyrocketed during the stimmy check period in 2021, at the same time banks were loosening standards. These things combined to boost actual money printing, banks making loans.

I'll grant that most analysts who claimed transitory did not have this nuance in their argument, but some of us did. The first half of the story generally goes like this: the economy was already slowing in 2019, COVID hit with a huge supply disaster, that was met by massive borrowing and spending from the government which boosted demand and causes some relatively small rises in lending/money printing.

Second type of transitory

His second type of transitory inflation is better and is as follows:

There’s another kind of transitory inflation, although it’s very different from what Team Transitory posited. Consider the effects of a massive monetary injection that occurs just once. The public would have much more cash and other liquid assets on hand than they’d like, so they reallocate their portfolios by spending down their excess money balances. This will boost demand for just about everything. Prices should grow more quickly than before. But eventually the price level will rise enough that the public will stop decreasing its stock of liquid assets. The higher prices are in general, the more money you need on-hand to make regular purchases. Here ends the inflationary episode. In the language of monetary economics, we transitioned from one price level growth path to another. The steps between the two growth paths contained elevated inflation. Since we transitioned from one equilibrium to another, the behavior of the economy over that interval might rightly be classified as transitory.

This is more correct IMO, however, is still missing a few pieces. First, the "monetary injection" needs to be paid back. It wasn't naked printing of unencumbered deposits. The government borrowed the money, and that debt must be serviced in the future. The difference between the present and that future repayment is a "transitory" period.

Using the term "monetary injection" masks the inherent transitory nature and leads to the idea that the new "equilibrium" being ceteris paribus. It is not. There was a trade-off with future consumption/economic activity. The demand was moved from the future to the present, prices rose, but that's not the end of the story. This transitory equilibrium requires further maintenance. If government spending does not continually grow, the completion of the move will be back toward pre-transitory price levels (with room for changes in demand profiles and capital structure that have occurred, like permanently shorter supply chains).

They can push this transitory nature off as long as they keep borrowing and spending, but the overarching pressure is back toward deflation.

I said this at the time. In 2022, after one year of the Biden administration in office, Janet Yellen went on Meet the Press to brag about cutting the deficit by $1.5 trillion. I pointed out at the time that this was going to lock-in transitory, because you need to continually pull demand forward to sustain economic activity and higher prices from a government spending enabled boom. I think they've realized this now, because the last 18 months has seen very high government spending again.

The second idea in the above quote is, "The higher prices are in general, the more money you need on-hand to make regular purchases." That is true, but where does that new higher flow of money come from? For instance, if prices rise by 10% but average incomes grow by only 2%, where is that money coming from to sustain the higher price level? Alex just says, "here ends the inflationary episode."

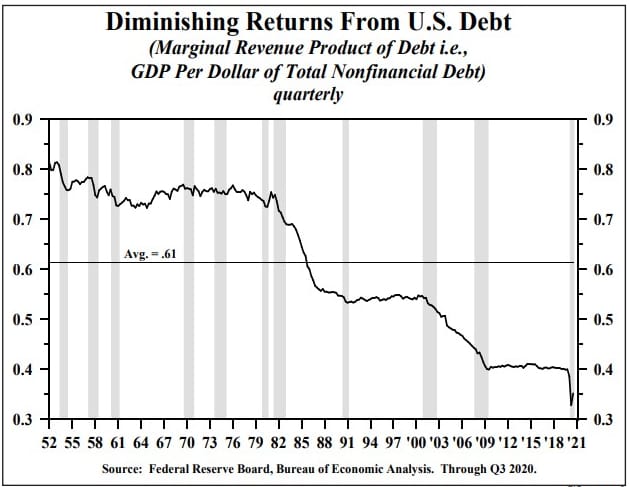

It typically first comes from savings in an attempt to maintain your standard of living and spending habits, but eventually it has to come from other discretionary spending. Consumers have to cut back, demand declines relative to supply and prices fall. It's a simple idea. If it requires $1000/mo to maintain your lifestyle, and you are paid $1000/mo we have "equilibrium." Now, if prices go up and it costs $1100 to maintain your lifestyle, you either have to supplement with savings, debt, or cut backs. Savings will run out, debt has to be repaid. There's no non-transitory solution for consumers. The only way to make it non-transitory is through increase in government borrowing and spending, which has diminishing marginal returns.

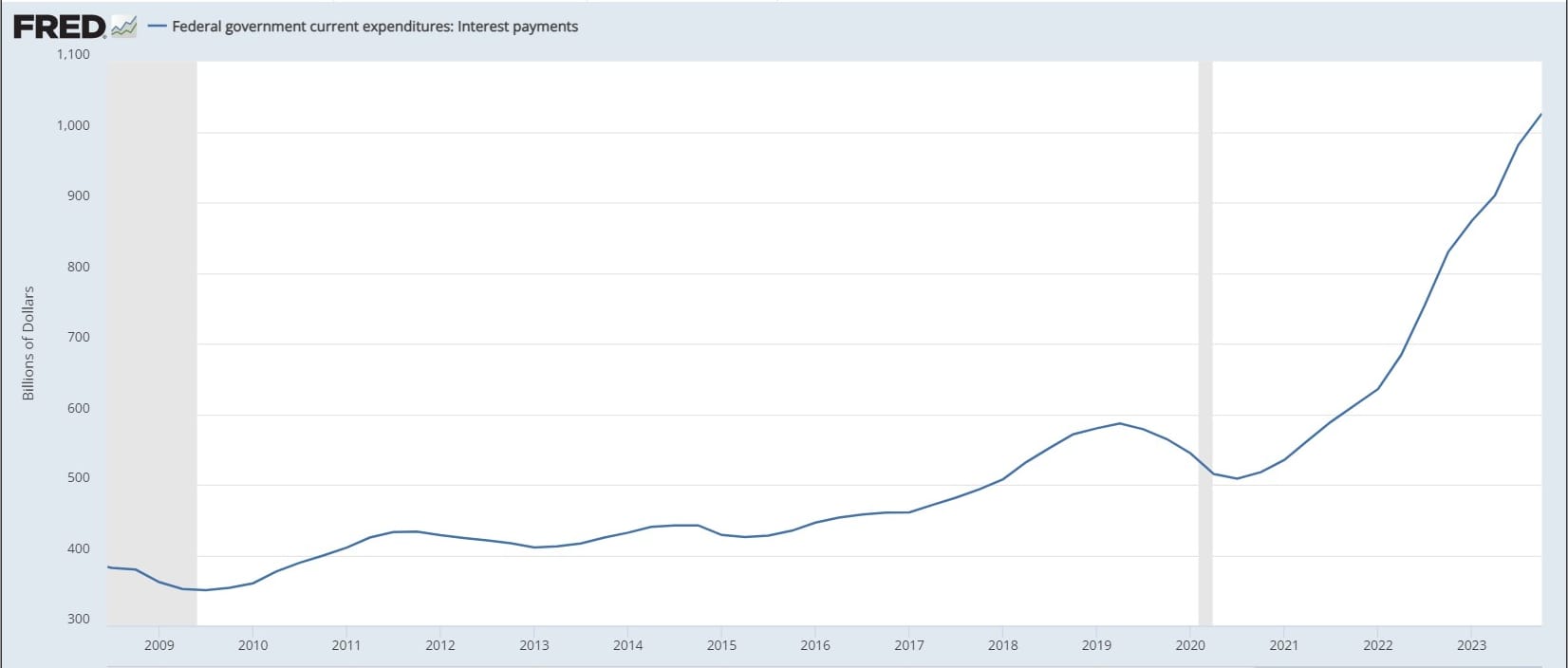

Policy intervention

Alex then spends a paragraph using policy interventions from the Fed to explain the transitory nature we've seen. I'll quickly point out that rates fell prior to the Fed cutting in 2019-2020, and rose prior to the Fed raising. Also, higher rates are an expense, but most economists overlook that they are also income. Think of interest payments as supplementing incomes. Since COVID, interest payments on government debt have risen 100%, from $500 billion to over $1 trillion. That is stimulus. Higher rates actually support higher levels of inflation because incomes rise.

Higher Fed policy rates also push economic activity out the risk curve. If you are only getting 0.25% income from your safest assets, you don't have as much confidence to take risks on less creditworthy borrowers (small business) where growth actually happens. However, if you are getting 5% from very safe assets, you are more willing to take risks on those small businesses. Higher yields are stimulatory in that way. Causing "inflation" to be longer lived than it otherwise would be.

Instead of another explanation for transitory, Alex is actually pointing out what made transitory take longer than expected.

Past inflations

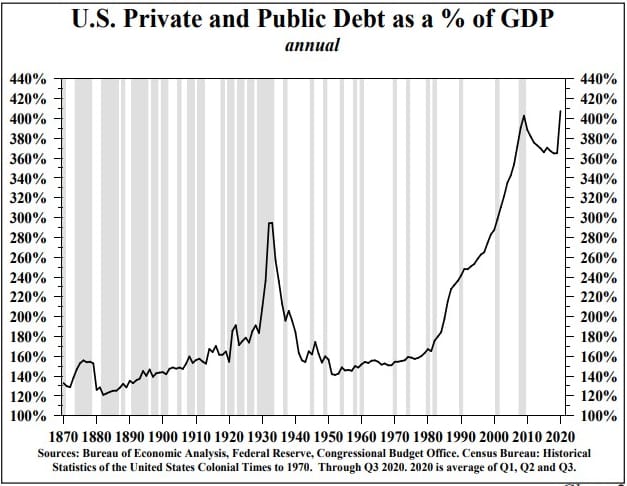

Alex then goes into the inflation of the 1970's and 80's as a case against transitory. Several things are wrong with this as well. First, that was a different monetary and economic environment. Debt levels were relatively low and there was low hanging productive uses for debt. There was high inflation in the 70's but there was also high real growth. 1976-1979 was the last period of sustained real growth over 5%.

Was this decade-long inflationary event transitory?

No, because there was sustained real growth. The marginal return on debt was extremely high, debt burdens were low, globalization and demographics were expanding. We were just starting on this credit-based money global debt-fueled boom. That is all over now.

Marginal revenue productivity of debt is in the toilet. Lacy Hunt of Hoisington Investments, has some great charts to show just where we are and how different it is to the 70's and 80's.

Conclusion

Transitory was right. Critics will straw man a monolithic Team Transitory, despite many of us having nuanced perspectives and reasons that combine supply-side, demand-side and monetary paradigm reasons. Alternative explanations for why CPI and PCE have been transitory are coping and wrong.

The underlying reason for transitory is ultimately a monetary realist one. The multi-decade credit boom is ending, global credit markets will shrink, deflationary pressures will rule. Each successive recession will result in lower growth and growth expectations until the credit-based system is redesigned, abandoned, or supplemented with sound money. Market participants will naturally migrate to sound forms of money which do not rely on elaborate credit architectures for their liquidity and value.