Roman and Byzantine Interest Rates - The Roman Empire 27 B.C. – 476 A.D.

Author: Kent Polkinghorne

Source material: A History of Interest Rates, Fourth Edition by Sidney Homer and Richard Sylla (1963, 2005). This book covers interest rate history dating back to ancient times and contains very interesting charts, tables, and analysis which I will attempt to modernize and summarize. This data can expand our understanding of different eras of monetary and financial information to make us better investors.

***

The history of Roman and Byzantine interest rates will be separated into three parts in order to align with major events in Rome’s history. The first part covered the Roman Republic, this second part covers the Roman Empire, and the third part will cover the Byzantine Empire.

Money and Banking in the Roman Empire

The transition period between the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire was marked by enormous dysfunction due to the Roman Civil War (49 B.C. to 31 B.C.) and, as a consequence, property rights were not respected during this time. Citizens reacted by hoarding money which had the effect of making it scarce and expensive. The end of the war and the subsequent reign of Augustus (27 B.C. to 14 A.D.) changed the fortunes of Rome for the better and money returned to circulation. The treasures of the recently acquired province of Egypt were coined and put into circulation and the volume of coin was expanded in general.

This all changed with the ascension of Tiberius (A.D. 14 to 37). Under Tiberius, monetary policy was reversed to a policy of reducing the amount of coin in circulation which resulted in hoarding anew. During this time, Rome was running a trade deficit with its trading partners and thus money had already been flowing out of the empire in order to pay for imported goods coming from the east. After the reign of Tiberius, monetary policy was reversed yet again. Under Caligula, Claudius, and Nero the minting of coins and the circulation of money were increased. It was also during this time that Nero began the infamous process of coin debasement, which would continue to plague Rome and ultimately play a leading role in its downfall a few centuries later as we will cover later in the article.

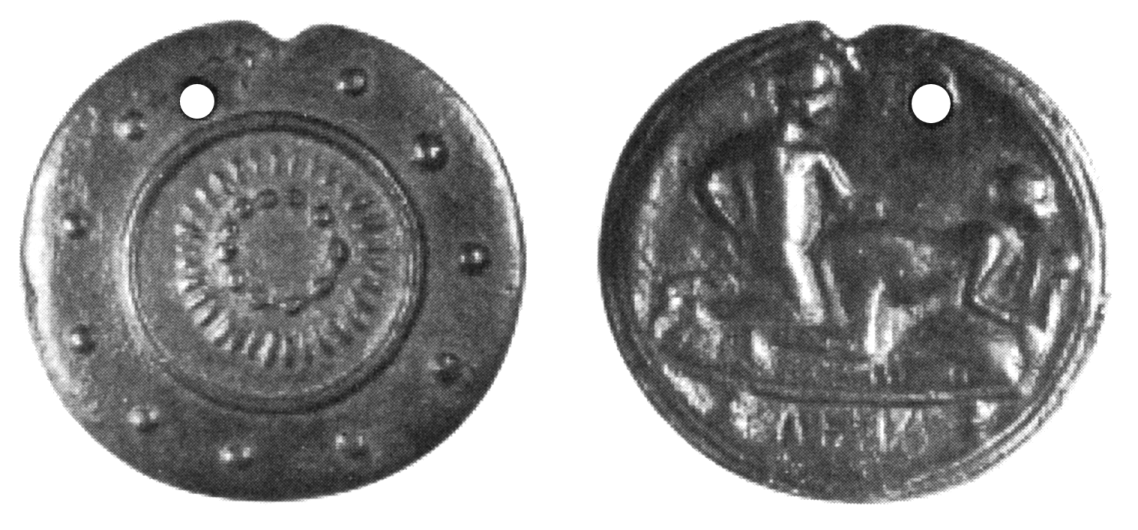

During the 1st Century, the metal content of coins was reduced by roughly 25% and then during the 2nd Century the percentage of dilution was even greater. Silver coins were eventually reduced to the status of token coins. Token coins were commonly made of cheaper metals and/or possibly used for brothels or perhaps for gaming. The Roman Spintria illustrated above is an example of a token coin. The 3rd Century was a time of great inflation. By the year 241 A.D. the Denarius had been diluted to just 48% of its original silver content and contained a meager 5% by 274 A.D.

Banking as an industry was not well developed in the Roman Empire as it had been in ancient Greece. Banking was seen as somewhat taboo by wealthier Romans so most profitable ventures were realized through either conquest or land investment.

Background on Credit in the Roman Empire

During the time of the Roman Civil War, the potential for confiscation made land ownership a dangerous proposition. We also know that money was being hoarded during this time from our section above. If we consider both instances together, we can safely assume that credit was severely contracted during the war. Fortunes would change with the arrival of Augustus, however, and credit would again begin to flow due to the restoration of property rights. After the civil war credit expanded, building activity grew, and the price of real estate rose. The large war debts were also liquidated causing interest rates to fall precipitously.

Tiberius' reign, first mentioned above, was the point at which credit expansion was halted and flung in reverse. Interest rates in ancient times often had legal maximas depending on the nature of the loan. The reduction in the money supply under Tiberius caused a spike in interest rates to levels beyond this legal maxima.

Despite the contraction of credit falling squarely on the shoulders of Tiberius, the bankers took the blame and, in response, bankers called in loans and contracted credit yet further. This led to a financial crisis in 33 A.D. which forced the hand of Tiberius. In order to end the crisis, Tiberius lent out his metal hoard on three-year terms interest free.

There are no historical records of industrial loans but there are reports of sea loans (loans for commercial maritime activity). Legal rates of interest did not apply to sea loans, likely due their risky nature, and rates are cited as high as 20% per voyage.

Under the reigns of Nerva (96-98 A.D.) and Trajan (98-117 A.D.) loans were advanced that were collateralized by land and the interest collected from said loans was used to support the poor. These loans were lent out at rates of 5%, a figure considered moderate at the time.

The legal maximum stayed in force until the 4th century A.D., through the reign of Constantine, but was increased to 12 ½% at some point thereafter. This was a period of time when the Roman Empire was fracturing and unstable. Lower rates were not again established until the 6th century A.D. under the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine Empire comprised the eastern part of what was formerly the Roman Empire and its’ capitol was situated in Constantinople (modern day Istanbul in Turkey). The history of Byzantine interest rates will be covered in next week’s piece.

Money and Credit in the Roman Provinces

Egypt

After the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 B.C., the province was purposely cut-off from international trade through the forced use of a fiat currency that only circulated domestically. The legal maximum rate of 12% in Rome also applied in Egypt and compound interest was forbidden. The accumulated interest on a loan was capped once the amount of interest reached the value of the principal. Using a modern example, if $100 is lent out over a period of time and accrues $10 of interest per month then the accrual of interest would cease ten months after the loan had been issued, at which point the total owed would be $200. Penalties on defaults in the Egyptian province could reach as high as 50%.

Penalties on defaults in the Egyptian province could reach as high as 50%. It is also recorded that pawnbrokers charged rates both below and significantly above the legal limit. Grain loans generated higher rates while seed loans generated lower rates. As illustrated in our chart below , wheat (grain) was the main export from Egypt. Despite its economic isolation, the extreme inflation occurring in Rome during the 3rd century A.D. managed find its way into Egypt as well.

Africa

The only recorded instances of credit in Rome’s African province, modern day Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco, related to endowment funds created by wealthy individuals for public purposes. Rates of interest were between 5-6%.

Asia Minor

Asia minor consisted of what is modern-day Turkey. Sacred, public, and private banks had been in operation prior to the Roman occupation, during the Hellenistic (Greek) period, and continued to operate under Roman rule as well. Temples accepted safe deposits and made some loans secured by real estate. Seed loans were also reported. Private banks would perform a number of functions such as money exchange and securitized lending and they also engaged in various business ventures. The 12% legal maxima that was imposed during the time of the Roman Republic continued under the Roman Empire. However, this rate of interest appeared to be too high which led Pliny to advise Emperor Trajan the following:

the money [of an Asiatic city] must lie [will continue to be] unemployed because no persons will borrow from the municipality at 12%

This quote implies that the common rates of interest were well below the legal maxima set by Rome. Trajan responded by agreeing to increase the amount of capital in circulation by offering lower rates on loans.

Explanation of Loan Categories in Chart Below

Legal Maxima: This was the maximum legal value of interest that could be charged; however, rates often exceeded this figure in practice.

Enforcing the legal maxima would have been very difficult in this era as evidenced by the interest rates on some of the loans depicted below in our chart. The maximum legal rate of interest also tended to fluctuate based on various circumstances. For example, in a political crisis or war interest rates would increase.

What is interesting is that interest rates often exceeded the legal maxima on the black (free) market and changes to the black market rates would preempt changes to the legal maximum.

Normal Loans: This category covers a broad range of loan types resembling those found in ancient Greece. During times of crisis, the interest rates on these loans could exceed the legal maximum. Loans were likely secured by land or real estate and of a short duration.

Interest Rates in the Roman Empire

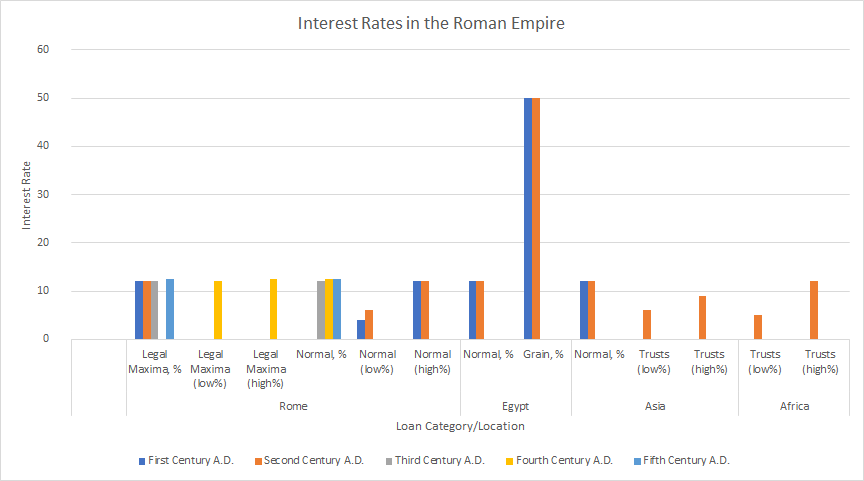

Our data on ancient Roman loans is based on a range of values. For example, the source material might mention rates were between 6 and 12% interest during a specific time period. In order to illustrate this in a chart the 6% end of the range would have an independent data point labeled as “normal (low%)” and the 12% end would have an independent data point labeled as “normal (high%). In reality, these values simply represent the boundaries on a range of interest rates for a given time period. The color of the bars in the chart refers to the century in which the data is relevant.

Interest rates remained within a range of 6-12% for centuries. The lone exception being the 50% rates charged in Egypt for grain loans. The relative political stability of the 1st and 2nd Centuries also affords us better information than we find later during more unstable periods.

The exact date of the fall of the Roman Empire continues to be hotly debated to this day, however, the abdication of Romulus Augustulus in 476, is widely accepted as the official end of the Roman Empire. That is the point at which the western part of the empire fell under the control of the Germanic tribes while the eastern part of the empire would continue and become known as the Byzantine Empire, which is where we will move for next weeks’ missive.